Of Unfounded Emotive Declarations and the Death of Queensland Adjudication

Those who make unfounded, emotive declarations should put up or shut up. Lexology readers deserve that such declarations be supported by empirical evidence.

The former adjudication registrar is again pursuing his old, tired agenda. He remains the sole voice supporting the indefensible proposition that the Building Industry Act (BIF) has been an effective tool assisting industry participants avoid insolvency when the Queensland number of adjudication determinations has dropped alarmingly.

He now introduces the unfounded and emotive term ‘adjudication shopping’ in his writing. Not only in the title to an article, but also the opening four paragraphs. A term used without reason. A term designed to evoke a negative reaction against Authorised Nominating Authorities (ANAs) at which it is directed.

The term is the building block for his defence of the continued appointment of adjudicators by the Queensland Adjudication Registrar. And what is the case? The former registrar’s case rests on the Murray report containing a section (section 13.2 Process for appointment of adjudicators’) which recognises the concerns of some over ‘adjudication shopping‘ and defines it as ‘the claimant chooses an ANA whose panel of adjudicators is perceived as ‘claimant friendly”.

Having quoted from the Murray Review, the former registrar does NOT say that the same report finds there is no credible evidence for the allegation of adjudication shopping. Also, he does NOT quote Mr Murray about the level of government oversight of ANAs.

Page 174 of the Murray Review

‘It needs to be emphasised that ANAs, whilst charged with the functions of receiving adjudication applications, appointing adjudicators and issuing adjudication certificates, are nonetheless subject to oversight by a relevant (state/territory based) government agency. The various legislatures that adopted the East Coast Model require the relevant government regulator to assess the financial and administrative capabilities of applicants wishing to become an ANA and upon being granted authorisation, to monitor the governance of the ANAs by ensuring that they adhere to the appropriate systems, procedures and reporting requirements and that any breach of good governance may result in the withdrawal of authorisation.’

Pages 180 - 181 of the Murray Review

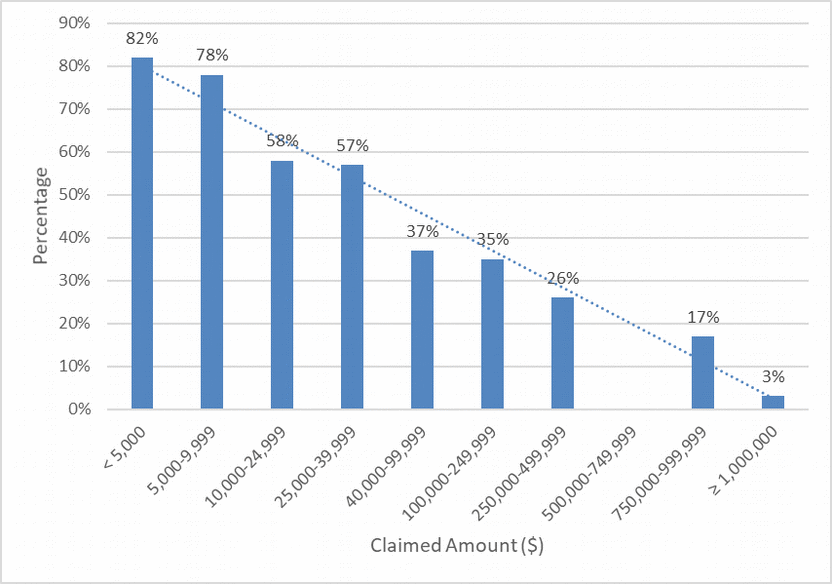

‘There has however been no credible evidence provided that would support the existence of the various allegations. Indeed, an analysis of the statistical data comparing the amounts claimed with the adjudicated amounts determined, discloses that a claimant’s success rate, expressed as a percentage of the claimed amount, is dependent on the degree to which the respondent has engaged itself in the adjudication process. In other words, where an adjudication application has been made in circumstances where a respondent has not provided a payment schedule, then the claimant is more likely to obtain an adjudication decision where the adjudication amount closely approximates the claimed amount. On the other hand, where an adjudication application has been made in circumstances where a respondent has provided a payment schedule (and subsequently an adjudication response) then the adjudicated amount expressed as a percentage of the claimed amount drops significantly. Further, the likelihood of a respondent providing a payment schedule is more likely to be greater as the value of the claimed amount increases. The following chart (Graph 1) extracted from Table 1 of the NSW Adjudication Activity Annual Report 2015/16 demonstrates this relationship clearly:

Graph 1: Percentage of claimants receiving the claimed amount, 2015/16

Source: Table 1 of the NSW Adjudication Activity Annual Report 2015/16

Nonetheless, the fact that I have not been provided with any evidence that would lead me to conclude that an ANA adjudicator appointment process is biased should not be the end of the matter. If ANAs are permitted to have a role within the adjudication process, the perception of bias cannot and should not be disregarded. It is undesirable that the integrity of the adjudication process be undermined by perceptions of bias. All participants should have confidence that the legislative regime that provides for disputed payment claims to be referred to adjudication will result in decisions that will not only be able to be made in a quick and cost-effective manner but that the process will, in all the circumstances, be seen to be fair.

Dismantling the role of the ANAs within the adjudication process would be equally undesirable because it would deprive participants (particularly small business subcontractors) of the free, but valuable, advisory service that appears to be best delivered by the ANAs. The security of payment legislative regime is both complex and highly prescriptive and accordingly those owners of ANAs that are willing to invest their private capital in order to provide such services should, subject to key governance and regulatory oversight, be allowed to operate. No doubt the criteria upon which a particular ANA should be authorised to operate will be dependent on a range of factors, including the systems and procedures for processing adjudication applications and the size, experience and reputation of the adjudicators on their panel. However, one of the most critical factors should be their capacity to provide a meaningful advisory service to participants.’

In addition to ignoring the Murray Review findings, the former registrar offers no evidence that adjudicator shopping has any basis in fact. There is no examination of the available statistics; and these are many statistics which were collected and published monthly by the former registrar.

My quotes from the Murray Review (above) raise two issues. Firstly, the degree of government oversight of the adjudicator appointment process including the conduct of ANAs and secondly, the need for evidence before ‘a meaningful advisory service to participants’ is removed.

In relation to government oversight, the former registrar boasts that he ‘prescribed additional conditions prescribing conditions on the registration of ANA’s which sought to address the need for independence in the referral of adjudication applications’. That is true. What is also true is that the former registrar never utilised these additional powers, at least that the ANA conducting the majority of Queensland nominations (Adjudicate Today) was made aware.

If the former registrar had reason to believe there was a problem, why did he not exercise his extensive new statutory powers to address the problem? Why, in the absence of taking action, did he then fight to become the sole nominating authority thereby providing his Office with additional powers, prestige, budget and staff. I believe he had no reason to exercise the new powers. Certainly prior to the scent of nationalising private sector businesses, without compensation, he was expressing nothing but support for the work of ANAs.

On 8 May 2009, the former registrar expressed his view on allegations of adjudication being claimant friendly. This view is most inconsistent to his current defence of the disastrous Queensland amendments that continue to fail industry participants.

Under the heading ‘Is adjudication claimant friendly’, the former registrar writes:

‘In my opinion the answer is a resounding “NO”.

...

Unfortunately a number of “myths” are circulating about adjudication, with the one that is absolutely without foundation and certainly the most potentially harmful being “claimants always get what they what in terms of payment outcomes under adjudication” or “adjudicators just “rubber stamp” what claimants want”.

The published statistics in this regard clearly does not support such a proposition. In fact it could be argued, based on the actual relevant published statistics that the adjudication process is now working against claimant!!!!

Let’s take a moment to review the actual published statistics in regard to decided adjudication amounts in relation to the amounts claimed (see attachment “A”, total value of claims released V total value of adjudicated amount (decisions released).

What does this graph tell us?

Of the 598 decided adjudication matters, where the total payment claims amounted to $159M, claimants in total were awarded $60M.

In terms of total adjudicated outcomes, Claimants in total only received 38% of what they were claiming.

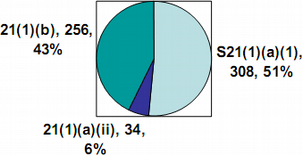

Further to the above published statistics, below is a table and graph that reflects a breakdown of these published figures, by drilling down to identifying under which “section 21 pathway” claimants lodged an adjudication application.

Section Decided Claimed Amount Decision Released Adjudicated 21(1)(a)(i) 308 $145,019,881.80 $50,952,316.21 21(1)(a)(ii) 34 $5,693,639.05 $2,461,139.63 21(1)(b) 256 $8,353,448.19 $7,071,387.98 TOTAL 598 $159,066,969.04 $60,484,843.82

What do these statistics tell us?

- Of the 308 adjudication applications decided where the respondent elected to actively participate in the adjudication process by serving a payment schedule on the claimant indicating an intention to pay less then what the claimant was seeking and giving reasons for adopting such a position (section 21(1)(a)(i)), total payment claims amounted to $145M but claimants in total were only awarded $51M.

- In terms of total adjudicated outcomes, claimants in total only received 35% of what they were claiming.

- Of the 256 adjudication applications decided where initially the respondent failed to actively participate in the adjudication process by serving a “first chance” payment schedule on the claimant (section 21(b)), total payment claims amounted to $8.4M, with claimants in total being awarded $7M.

- In these smaller, at least initially “non contested matters”, claimants in total received 83% of what they were claiming.

What do these statistics tell us?

- Quite simply, where respondents choose to participate in the adjudication right from the beginning of the process and provide relevant, timely and meaningful information to claimants, adjudicators are displaying a strong propensity to examine with a serious degree of rigour (as they should do) the total amount being sought by the claimant and reject any unsubstantiated claimed items.

- However where respondents choose to ignore payment claims and not provide a response by way of a valid payment schedule to claimants within 2 weeks (10 business days) of receiving such a claim, then they are forgoing their initial right to participate in the adjudication process.

While I have not reviewed the extent such respondents availed themselves of the opportunity in such circumstances to belatedly partake in the adjudication process, my personal observations are that only a few respondents take the opportunity to provide a valid, relevant and meaningful “second chance” payment schedule. Consequently, the fact that claimants are overwhelming successful in such matters should surprise nobody.’

The Murray Review looked at updated statistics and arrived at the same conclusions.

I would have liked to provide a full analysis of the current adjudication statistics to measure the degree to which adjudicators are leaning to respondents over claimants in Queensland, but this is not possible since the current Adjudication Registrar has withheld the monthly publication of adjudication statistics since December 2018. I invite the Adjudication Registrar to reconsider that decision.

Latest Articles

MAJOR AMENDMENTS SLATED FOR VICTORIA’S SOP ACT

October 25, 2024

Will the drafting of the BIF Act kill adjudication in Queensland?

October 21, 2024

IS IT “BACK TO THE FUTURE” FOR QLD ADJUDICATIONS?

February 07, 2024

Victorian Security of Payment Act: Amendment effective 1 February 2024

February 01, 2024